Rudolph Nester was born in Baden, Germany in 1856. In 1873, at the age of 17 he emigrated to the US. In 1880, he married Mary Heembrock, the daughter of an established German-American farmer from St. Charles, MO. Later that same year, the 1880 census has them farming in Dora Township, Otter Tail County, MN. Apparently, Rudolph was able to get work, woo a woman and make enough money to stake a new homestead in the 7 years since he emigrated.

The claim was 160 acres of bare land between West Spirit Lake and Otter Lake. Otter Tail County was previously the home of Ojibwe and Dakota people. The last remnant of Ojibwe, members of the Pillager Band, moved to the White Earth reservation after it was established in 1868. Rudolph and Mary patented the homestead in 1885. Mary’s brother John received a patent for an adjacent claim in 1890. Most of their neighbors appear to have been fellow German immigrants, with names like Schimmelfenig, Wagner and Klug.

Rudolph and Mary had a big family: 9 children (8 who survived to adulthood) between 1881 and 1898. Devout Catholics, they may have attended Mass at Dora Catholic Church, which was located about 3 miles to the southeast. Oldest son Joseph went west to find his fortune; his WWI draft card has him in Montana working as a stone cutter.

As second son Emil came of age, Rudolph decided to buy land that had recently become available on the White Earth reservation as a result of federal legislation (see blog post “A Model Reservation”). He may have purchased the land from Zoe (Zoway) Fairbanks, the original allotee. Zoe was issued the allotment in 1889 and patented it in 1902. A plat from 1904 shows her ownership.

The parcel Rudolph bought was 75 acres on the north end of Fairbanks Lake, about 4 miles south of the White Earth agency. It’s not clear whether the land had been cleared or plowed or whether Zoe Fairbanks lived there before the sale. In family stories, Emil is said to have spent a year there before getting married. It may be that he cleared land and built a home there during that year. Today, the land is partially forested and partially cultivated.

On February 11, 1911 Emil married Annie Poss, daughter of Jacob Poss (Paas) who farmed along the north shore of Lake Lizzie in Otter Tail County. They moved to the Fairbanks Lake property and began their family. Their first four children, Alice, Lucille, Irene and Clifford were all born on the farm.

The Nesters attended Mass at St. Benedict’s Mission, located two miles north of their farm. The Mission was run by Fr. Aloysius Hermaneutz, OSB who served the people at White Earth for over 50 years. The older children attended school at the Mission. The family witnessed the wholesale transfer of land from the White Earth Ojibwe to white settlers firsthand. This period was a dark chapter in the history of the reservation as tribal members lost the land base they needed for subsistence.

In 1919, Emil and Annie sold their farm and auctioned off all the equipment and livestock. They moved into the new town of Callaway and joined Assumption Catholic Church. Emil went into business as a butcher with Harry Hanson, another former farmer. Eventually, Emil bought out Harry and owned the business, which included a meat market, outright. By 1923, Emil was part-owner of a movie theater in the bustling town. After Prohibition ended in 1933, Emil opened a “beer parlor” by partitioning off part of the meat market.

As with many small towns, Callaway suffered during the Great Depression. Emil was forced to close the meat market. The movie theater was no longer operating and the beer parlor became Callaway’s first municipal liquor store. Emil managed it for a short time. He also continued custom butchering, traveling from farm to farm.

At about this time, Emil and Annie’s daughter Irene or “Diz” (short for Dizzy) began dating a young man named Bud who lived on a farm north of town. Bud’s parents had also experienced adversity, having the lost the farm in the late 1920s. Pete and Addie rented it back from the state and raised their 10 children there.

Although Bud’s family attended the same church, they didn’t move in the same social circles as the Nesters. In fact, when Bud and Diz announced their engagement, Emil was not happy because Bud was an Indian. Emil forebade members of the family from attending the wedding. This kind of prejudice was not unusual around the reservation at the time.

Immigrant families flocked to White Earth in the land rush that resulted from the federal allotment policies. For these families, owning land meant having the opportunity to establish and better themselves in their new country. They could not understand why tribal people did not take advantage of their “opportunity” to become farmers.

The few tribal members who did become farmers were mostly the mixed-bloods, like the Sprys. Although they were living and working hard like their white neighbors, they could not escape being painted with the same brush as the more traditional tribal people who depended on subsistence. They were all “lazy Indians” in the eyes of some whites, apparently including Emil.

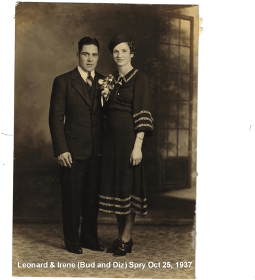

Bud and Diz were married on October 25, 1937. Bud’s brother Elmer and Diz’s cousin Alice Lefebvre were the witnesses. One of Diz’s sisters, probably Hazel, snuck out of the house to attend.

Bud and Diz got off to a rough start. Bud had started working at Johnson’s Bee Farm in Callaway but it was seasonal work. To make ends meet, Bud worked in the woods in the winter months, cutting firewood to sell. At one point, to save rent money, Bud built a log cabin near St. Clair Lake.

After a couple of miscarriages, Bud and Diz welcomed a son, Jerry (my dad) in 1939. Jerry was born in the old White Earth Indian Hospital. Because he was a bit premature and very small, the nurses put Jerry in a shoebox on the mantle of the big fireplace in the main lobby of the hospital. The nurses doubted he would survive but he did. Bud and Diz brought Jerry home to the little cabin. Diz recalled melting snow in the winter for baths and laundry. She had to learn to cook and bake without eggs. It was primitive living but they had lots of company; their friends came by to see how they were doing and to play cards. They were happy.

Eventually, Bud and Diz and their family moved into Callaway. They rented the upstairs of a small home, next door to Emil and Annie. Bud continued to work at Johnson’s Bee Farm. Although they were next-door neighbors, Bud and Emil didn’t talk. Emil refused to acknowledge Bud as his son-in-law.

Life went on for the Sprys as their little family continued to grow. Bud was a good baseball player and played for Callaway’s town ball team in those days. He was known as the left-handed catcher who batted from the right.

When WWII started, Bud and Diz had two small children: Jerry and his sister Cleo. Bud apparently was deferred in the draft as a father. His brothers Elmer, Lee and Ervin (Bunt) all served. As for Emil, family lore has him working on the Alaska Highway construction project as a cook. Later in the war, Emil and Annie both worked at the Hanford Works, which was part of the secret Manhattan Project. According to Grandma Diz, they worked in the mess halls, Emil as a butcher and Annie preparing vegetables. (Side note: 50 years later I was working at Hanford in an office building built on the site of one of the work camps.)

Finally, back home in Callaway Emil and Annie resumed their lives. One day Emil noticed a little boy playing with a red wagon on the sidewalk in front of his house. He was handsome little guy, with dark hair, his mom’s blue eyes and a quick smile. Emil and Annie invited the boy into their house. That little boy was Jerry, who eventually won his Grandpa over. Soon Bud and Emil were on speaking terms and eventually became close friends.

Later in the 1940s Emil was in a terrible car accident. He never fully recovered from his injuries. In his last days, the only person Emil wanted at his bedside was Bud.

In this time of COVID-19, many are learning to slow down, take more notice of things around them and appreciate what they have. Even for me, someone who has been retired for several years and has all the time in the world, there seems to be a slower pace.

In this time of COVID-19, many are learning to slow down, take more notice of things around them and appreciate what they have. Even for me, someone who has been retired for several years and has all the time in the world, there seems to be a slower pace.

During my first few trips out (we are asked by the DNR to visit once a month, if possible) I was mystified by the lack of grass. The ground was densely covered with forbs (leafy plants) and woody species like like willow and aspen. Grass seemed to be only a minor component of the plant community, which went against my idea of what prairie should look like. Finally, when I visited in August I encountered the “sea of grass” I had imagined. Big bluestem and Indian grass stood shoulder-high, towering over the other plants. These are called “warm season” grasses, which don’t even begin growing until July. I realized I had been looking in May and June for the “cool season” grasses I was used to seeing in drier grasslands out west.

During my first few trips out (we are asked by the DNR to visit once a month, if possible) I was mystified by the lack of grass. The ground was densely covered with forbs (leafy plants) and woody species like like willow and aspen. Grass seemed to be only a minor component of the plant community, which went against my idea of what prairie should look like. Finally, when I visited in August I encountered the “sea of grass” I had imagined. Big bluestem and Indian grass stood shoulder-high, towering over the other plants. These are called “warm season” grasses, which don’t even begin growing until July. I realized I had been looking in May and June for the “cool season” grasses I was used to seeing in drier grasslands out west.