Last October, my wife and I decided to make trip back to Madeline Island to celebrate our anniversary. We had been there several years ago and really enjoyed our time there. I also wanted to go back because the Madeline Island Museum was closed last time and I wanted to see if they had any information about my ancestors.

We stayed in Bayfield and took the ferry out to LaPointe. The museum was open this time. I told a staffer at the front desk that my great-great-great grandparents were married there. She offered to make photocopies of pages from the marriage register, which had been compiled and typed from the original register. I got a copy of the page listing the marriage of Pierre Trotochaud to Angelique Masset (or Massey) by Father Baraga in 1843. Interestingly, Angelique was listed by her mother’s maiden name and not Blair.

While touring the museum, I stopped to talk with an elder from the nearby Red Cliff Reservation named Rob who worked there. I told Rob about the marriage record. He said the names sounded familiar to him. Then he showed me a photo of a book on his phone, “All Our Relations”. Rob suggested I check it out to see if I could learn more about my family.

Rob went on to tell me about the importance of the island (called Mooningwanekaaning in Ojibwe, referring to home of the yellow-shafted flicker) to the Ojibwe. He told me that many of the people who migrated from the island to Sandy Lake, where Angelique was from, were of the Loon Clan. Rob explained that, although the Ojibwe had dispersed from Mooningwanekaaning to reservations established by the treaties, they still considered the island their spiritual home. Rob pointed out that many of Catholic Indians continued to return to the island to have their children baptized and to be married. He mentioned two children buried at the Catholic church who perished at Sandy Lake and their parents buried them at LaPointe. (These were Clem Beaulieu’s two daughters who died in 1845.) I enjoyed my visit with Rob and told him I hoped to see him again.

When I got home I immediately reserved a copy of “All Our Relations” from the local library. Rob was right: the book had information about our family. The book includes records of interviews conducted at LaPointe after the Treaty of 1837. The government was trying to determine who was eligible for a payment to mixed bloods that was provided for in the treaty.

One of the interviewees was Margaret Bles (Blai or Blais), who was born at Pine River in Iowa Territory, which at that time included most of what is now Minnesota. She had resided at Sandy Lake “until within the last 2 months.” The entry went on to say that she married a man named Alexis Bles “13 or 14 years since”, which would be about 1825. The marriage produced 5 children: Angelique, 11 yrs old; Antoine 10; Joseph 8; Edouard 6; and Alexander 4. Antoine had been born at Mille Lacs and Joseph at Leech Lake; the other three children were born at or near Sandy Lake. This record matches the names and approximate ages of the Blairs in our family tree. The record also mentions that Alexis had died “4 years since.” This would be about 1835.

The book also includes information about a man named Alexis Blais who appeared before the Indian agent in 1828. He was one of three men who were ordered out of Indian country the previous year because they did not have licenses to trade in Indian country. The men were summoned to Sault Ste. Marie by the agent, none other than Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, the “discoverer” of the Mississippi headwaters. The episode is documented in Schoolcraft’s “Personal Memoirs”, which includes parts of his daily journals. Schoolcraft wrote that Alexis “pleaded ignorance” to the laws pertaining to traders and Indian country. Schoolcraft’s journal implies that Alexis was the subject of a complaint by “Mr. Aikin” at Sandy Lake. That would be William Aitkin, the trader who ran the American Fur Company post there. During the interview, Alexis guessed that he would not have gotten in trouble if he had worked for Aitkin instead of independently. According to Schoolcraft, Alexis “did not desire to return to the Indian country”.

If Alexis Blais did leave the area in 1828, he would not have fathered Margaret’s younger children. In her interview at LaPointe Margaret claimed he died around 1835, which suggests he did not leave after meeting with Schoolcraft but returned to his family.

This experience has finally cleared up the mystery of who Alexis Blais (Alexander Blair) was and gives me a better picture of what life was like for Margaret and her children. It appears they moved wherever Alexis could make a living, with stops at Leech Lake and Mille Lacs. It is fascinating to to know that our ancestors interacted with historic figures like Schoolcraft, Baraga and Aitkin.

Mooningwanekaaning was important to the family; Margaret and her children were baptized there by Father Baraga later in 1839 (documented in “All Our Relations”). Now the island holds a special place in my heart, too.

Despite a disastrous farm economy and the Great Depression, Pete and Addie managed to raise their kids and send them off into the world to start their own families. Pete lost Addie in 1944 at the age of 65. Pete lived the rest of his life in Callaway in a house on the south side of town. He passed away in 1971, at the age of 88.

Despite a disastrous farm economy and the Great Depression, Pete and Addie managed to raise their kids and send them off into the world to start their own families. Pete lost Addie in 1944 at the age of 65. Pete lived the rest of his life in Callaway in a house on the south side of town. He passed away in 1971, at the age of 88.

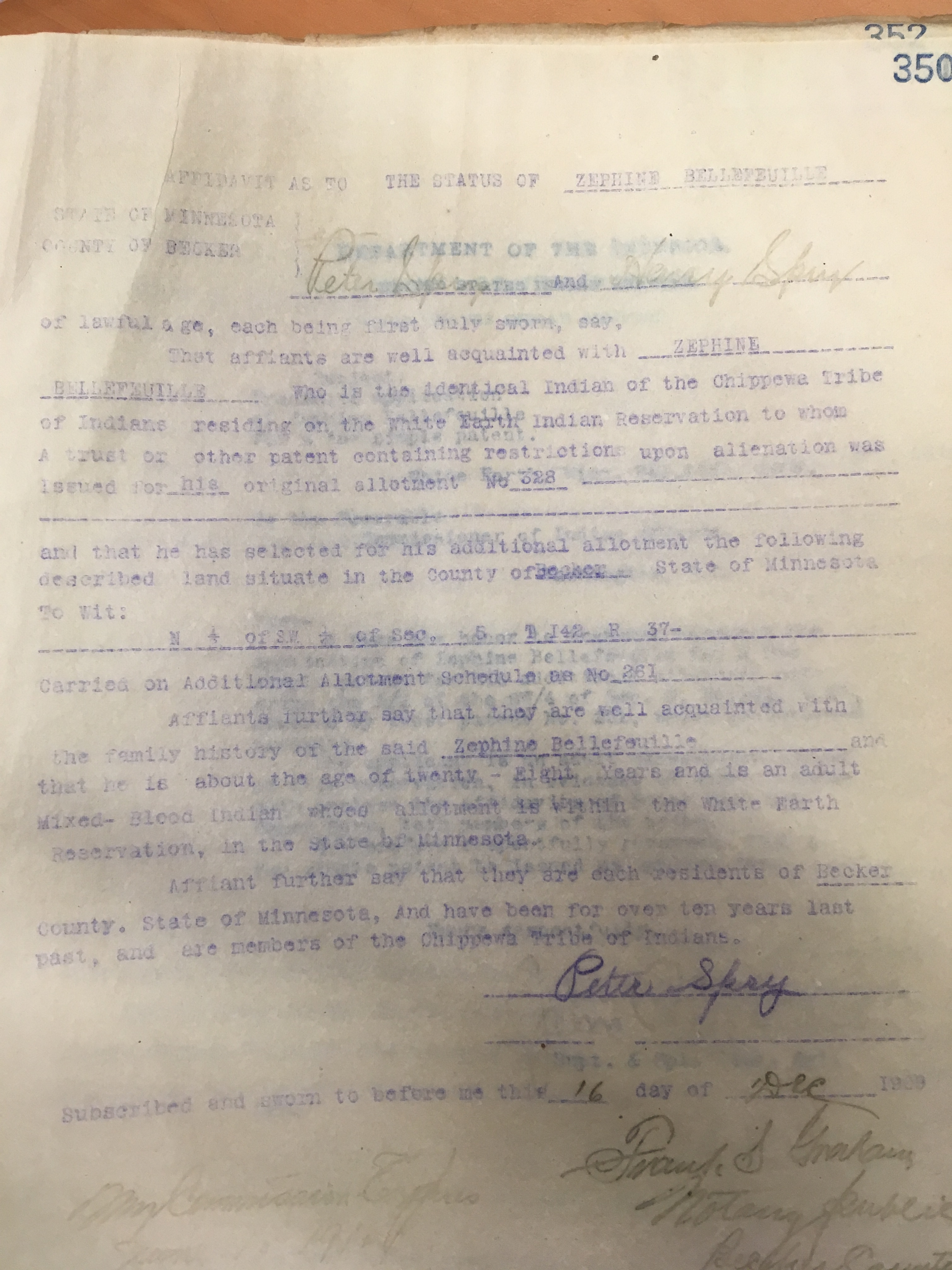

Finally, I reviewed records associated with the land fraud claims and investigations made at White Earth in the early 1900s. I came across a record (case no. 145) wherein Lawrence Spry mortgaged his additional allotment in 1909 for $800 to the Homestead Real Estate Loan Co. It is not clear whether this was proven to be a case of fraud (Lawrence was 18 or 19 at the time).

Finally, I reviewed records associated with the land fraud claims and investigations made at White Earth in the early 1900s. I came across a record (case no. 145) wherein Lawrence Spry mortgaged his additional allotment in 1909 for $800 to the Homestead Real Estate Loan Co. It is not clear whether this was proven to be a case of fraud (Lawrence was 18 or 19 at the time).