A few years ago, I had heard there was a trunk or box that contained some of Grandpa Pete’s possessions in the possession of my cousin Ernie. It took me a year or more to connect with Ernie, who told me he had the trunk but there was nothing in it. He didn’t know what had happened to its contents, which he said once included “Uncle Lee’s Bronze Star.” That information sent me on a journey to find out more about my great uncle.

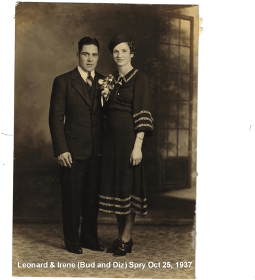

Leopold Anthony Spry was born April 4, 1916 to Peter and Adelaide Spry on their farm north of present-day Callaway (see blog post “Prosperity and Hard Times in Callaway”). Lee likely grew up doing farm chores with his siblings. The 1940 census shows Lee at age 24 still at home and working as a farm laborer, probably for neighbors as his parents no longer had the farm. He registered for the draft on 16 October of that year, along with his brothers Ray, Bud (Leonard) and Bunt (Ervin) in Callaway. Interestingly, brothers Elmer and Ernie also registered that day at Grand Portage in Cook County. It seems the brothers were united in doing their patriotic duty. Of these, Lee, Elmer and Bunt all served in World War II.

I tried to retrieve Lee’s military records from the National Archives but learned that most WWII Army personnel records were destroyed in a fire in 1973. All they sent me was his final pay stub. I didn’t have much hope of learning more about Lee’s military service. Then one day last summer I came across a Facebook post about Twisted Twigs Genealogy, who specialize in tracking down records for military units at the National Archives. I sent in a request to have them search for Lee’s records and waited.

Earlier this year, I was notified that Twisted Twigs had completed their search and that I would be receiving an electronic copy of a 227-page “OMPF Mini Reconstruction File.” It took a few email exchanges but I had finally gotten what I was looking for.

The records do not indicate where or when Lee received basic training. In October 1942 Pvt. Lee Spry was transferred to the 23rd General Hospital at Ft. Meade in Maryland. The bulk of the 227 pages were monthly company reports containing head counts and notes about various enlisted men reporting for duty on each day. Also included were “Ration Accounts” that listed men who were authorized to mess separately. Pvt. Spry showed up on these lists from time to time. Apparently, these were personnel who received a cash allowance for subsistence away from their base during training and other assignments. Pretty mundane stuff.

The Reconstruction File included a history of the 23rd General Hospital, which shipped out to Africa in late July 1943. They arrived in Casablanca, Morocco in August and spent that summer and fall hopscotching across North Africa by train finally to Oran, Algeria where they prepared to be deployed to Italy. On 28 October the unit landed on the beach outside Naples because the harbor was strewn with wreckage. The beach was mined by the Germans and several people were injured and one killed crossing the beach. They marched to a large fair grounds and set up a hospital among some bombed-out buildings. The 23rd General Hospital received its first combat-wounded patients on 17 November 1943. The hospital served over 11,000 patients over the next six months. It’s not clear what Pvt. Spry’s duties were; perhaps he served as an orderly in the hospital.

On 30 May, 1944, Pvt. Spry was assigned to Company A of the 310th Medical Battalion, which was preparing to support the 337th Infantry Combat Team of the 85th Infantry Division. The 310th was responsible for evacuating wounded soldiers from the battlefield and providing initial medical care. Pvt. Spry was assigned to be a litter bearer. On 5 June, the infantry and the litter bearers marched through Rome to the cheers of its residents.

On 13 September US and British troops began their assault on the Gothic Line, which was a fortified line of defense built by the Germans across the mountains of central Italy. The Gothic line included over 2,000 machine-gun nests, over 400 artillery positions and 130,000 yards of barbed wire. The 337th, supported by the 310th, was assigned to take Mt. Pratone, located northeast of Florence.

The following is an excerpt from “Highlights of Company A, 310th Medical Battalion”, a report included in the online history of the 337th Infantry Regiment:

…Casualties were heavy and conditions for evacuation unbelievably difficult. Our litter bearers at times carried patients for as many as six to eight miles over almost impassible mountain trails, across narrow paths gouged out of sheer cliffs…Many times one false step meant death.

The experience of T/5 Sol Glik and his squad of three consisting of Pvt. John Schaffer, Pfc. Thomas Shipp and Pvt. Leopold Spry is an indication of the heroism and physical strain demanded of the men in effecting hand evacuation. Sol and his squad volunteered to accompany an assault unit in an early morning attack. While yet a considerable distance from their objective the unit was fired upon and split into two sections by Jerry (Germans) who was dug in on the side of a nearby dominating hill…Both infantry and medics alike were pinned to the ground. Word of a casualty eventually reached the squad and the men were forced to abandon whatever cover they had to find the casualty, gave what aid they could, and prepared to carry him back to the aid station by a round-about route…This return route involved the crossing of two mountain peaks. It was only with superhuman effort that the squad finally completed the unfamiliar, eight miles evacuation over terrain hazardous in itself, not to mention the difficulties imposed by intermittent enemy artillery and mortar barrages. It was for this achievement that Sol Glick and his squad were awarded Bronze Star medals.

The official record of Bronze Star awards was included in the Reconstruction File. It reads as follows:

LEOPOLD A. SPRY, (37292274), Private, Medical Department, Company “A”, 310th Medical Battalion, United States Army. For heroic achievement in action on 17 September 1944, in Italy. Entered military service from Callaway, Minnesota.

Pvt. Spry continued to serve with the 310th Medical Battalion in Italy through the end of the war and was discharged on 27 October 1945.

Unfortunately, I have little other information about Uncle Lee’s life after the war. According to the 1950 US Census, he was living in White Earth with a woman named Cynthia listed as his wife. This would be Cynthia Leecy, the daughter of John Leecy who had a store in White Earth. I have not found a marriage record for Lee and Cynthia. The census has Lee working as a farm hand.

On 23 May 1958, Lee Spry took his own life in a house in Callaway. According to my dad, Grandpa Bud had to clean up the blood and gore. Dad doesn’t remember much about Uncle Lee, other than he drank a lot. These days we are all familiar with PTSD among veterans. Although we’ll never know, it’s possible that Uncle Lee was haunted by what he saw during the war.

Uncle Lee’s grave is located at St. Mary’s Cemetery in Callaway. When my parents had responsibility for maintaining the cemetery, Dad said he always made sure there were flowers at Uncle Lee’s grave. Other veterans in the cemetery have an official veteran’s headstone or plaque that lists their rank, period of service and branch of the military. Uncle Lee’s grave marker is just a simple stone. There is a stake with a star indicating he was a veteran. Perhaps the family didn’t know that Lee qualified for a military headstone.

It’s more likely they were following the teachings of the Catholic Church at the time, which considered suicide a mortal sin. That is why Uncle Lee was buried back in a far corner of the cemetery. Thankfully, the Church has modernized its views and recognizes that suicide is often due to mental illness. By sharing his story, I’m hoping my family will change their views on Lee and recognize his illness.

I would really like to see Lee’s grave marked with a military headstone, but I don’t know if that’s possible.

In this time of COVID-19, many are learning to slow down, take more notice of things around them and appreciate what they have. Even for me, someone who has been retired for several years and has all the time in the world, there seems to be a slower pace.

In this time of COVID-19, many are learning to slow down, take more notice of things around them and appreciate what they have. Even for me, someone who has been retired for several years and has all the time in the world, there seems to be a slower pace.

Despite a disastrous farm economy and the Great Depression, Pete and Addie managed to raise their kids and send them off into the world to start their own families. Pete lost Addie in 1944 at the age of 65. Pete lived the rest of his life in Callaway in a house on the south side of town. He passed away in 1971, at the age of 88.

Despite a disastrous farm economy and the Great Depression, Pete and Addie managed to raise their kids and send them off into the world to start their own families. Pete lost Addie in 1944 at the age of 65. Pete lived the rest of his life in Callaway in a house on the south side of town. He passed away in 1971, at the age of 88.

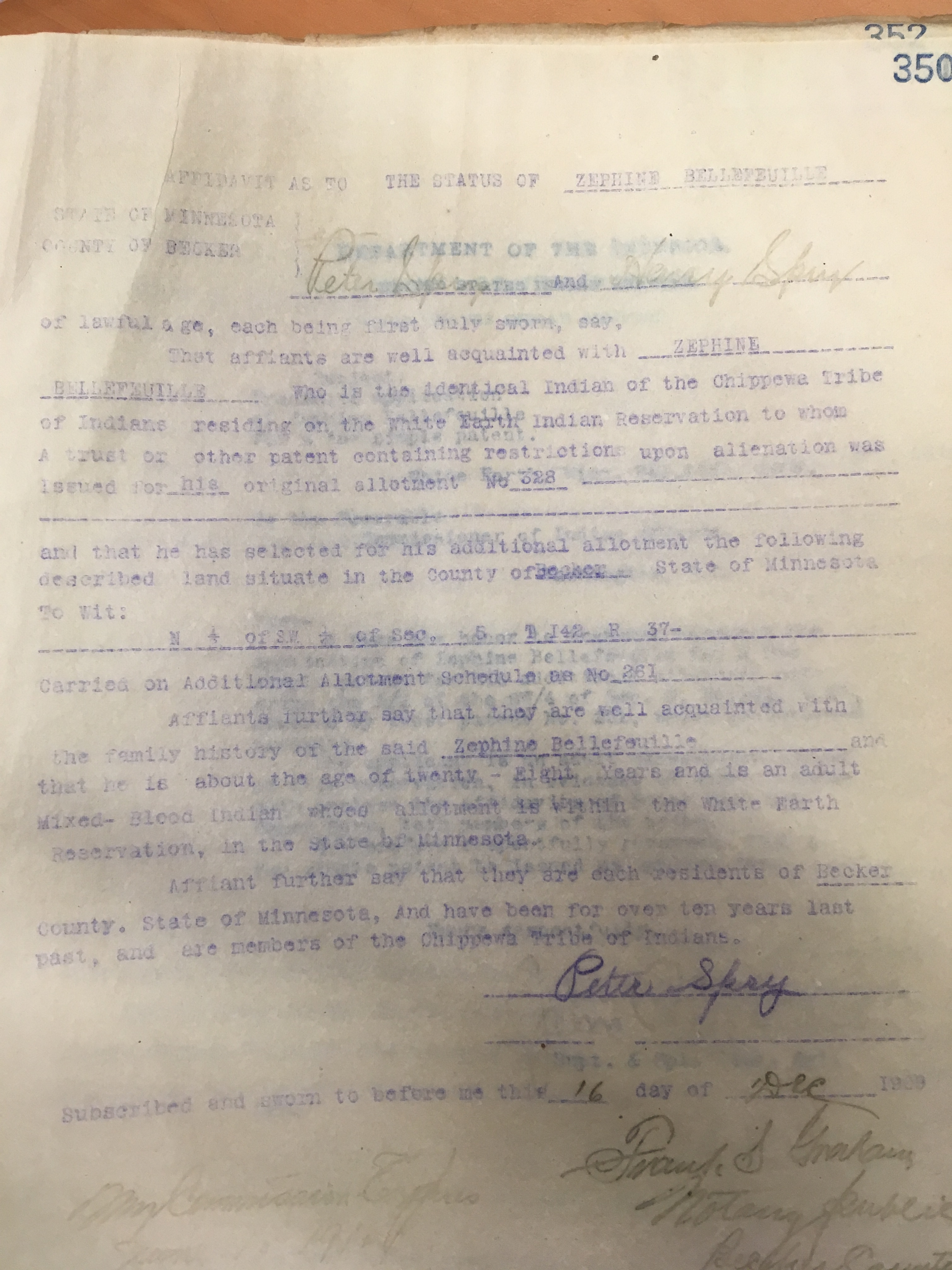

Finally, I reviewed records associated with the land fraud claims and investigations made at White Earth in the early 1900s. I came across a record (case no. 145) wherein Lawrence Spry mortgaged his additional allotment in 1909 for $800 to the Homestead Real Estate Loan Co. It is not clear whether this was proven to be a case of fraud (Lawrence was 18 or 19 at the time).

Finally, I reviewed records associated with the land fraud claims and investigations made at White Earth in the early 1900s. I came across a record (case no. 145) wherein Lawrence Spry mortgaged his additional allotment in 1909 for $800 to the Homestead Real Estate Loan Co. It is not clear whether this was proven to be a case of fraud (Lawrence was 18 or 19 at the time).